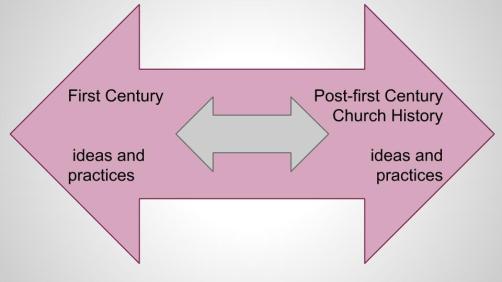

When Christians think about church history and the church today, there are a continuum of viewpoints with extremes at either end. On one side of the continuum we would have:

Those who hold the past 2000 years of church history to be sacred and binding tradition,

and on the other side:

Those who want the body of Christ to exactly replicate the practices of the first century believers, and view any ideas or practices developed since that time as unwanted baggage.

Roman Catholic doctrine, for instance, is heavily influenced by the ideas and practices of the Early Church Fathers, as well as all of the Popes for the past 2000 years. Every time a Pope has spoken ex cathedra, whatever he has said has become part of church law from that point forward (more or less.) Roman Catholicism would definitely be somewhere on the “church history” end of this continuum.

Roman Catholic doctrine, for instance, is heavily influenced by the ideas and practices of the Early Church Fathers, as well as all of the Popes for the past 2000 years. Every time a Pope has spoken ex cathedra, whatever he has said has become part of church law from that point forward (more or less.) Roman Catholicism would definitely be somewhere on the “church history” end of this continuum.

Protestantism, on the other hand, was born with a certain consideration given to the First Century as more weighty than the words of succeeding popes. The entire doctrine of Sola Scriptura, a cry of the Protestant Reformation, was in essence a statement that, “What we really need is first century apostolic teaching and practice.” Some groups have gone as far to this end of the arrow as they can get; I have been part of church groups where the main dream is to do everything the exact same way as the first century church would have done it.

The charismatic and pentecostal nod to this is the miracles and spiritual gifts that are recorded in the first century Biblical record; getting back to the power and glory of the early church means restoring the practice and function of these gifts in the church. But there is also a nod towards a continuuing history of the church when charismatics talk about how “the latter rain shall be greater than the former.” Additionally, the practices of charismatic church services are often not at all about returning to the first century but rather being as relevant to current culture as possible; therefore amped sound systems and cool lighting effects are completely acceptable in many charismatic church forms. But charismatics are often quite frightened by church traditions from earlier eras – liturgy, for instance, developed from prior centuries is somewhat suspect of being dry and dead formula, unworthy of current use. Some groups have delved into writings of groups devoted to meditation and prayer, such as the Desert Fathers and various monks and nuns from the past, as these groups and people had mystic practices and experiences resembling the practices of modern charismatic intercessory prayer and visionary ecstasies. But by and large, church history is suspect of being full of bad doctrines and religiousity, and overall, is just a very long time period that is best mostly forgotten.

Older Protestant denominations such as Lutherans and Quakers and Episcopalians/Anglicans have been around long enough to have their very own “church histories” irregardless of the broader sense of church history from before they were founded (or the church history of other denominations after they were founded.) So Anglicans can enjoy the richness of the “Book of Common Prayer” for instance and feel a sense of connection with a worldwide body of Christians both presently and those from the past who prayed the same prayers regularly.

Each denomination tends to have its own practices (the histories or even presence of which worshippers are generally not identifiably aware, as things such as pulpits or choirs or offering plates are just taken for granted as default practices) and many practices such as these do vary from the methodology of the New Testament era Christians. And this is also true of other groups of Christians off from the Western lineages I have been discussing, such as Eastern Orthodox or Maronite or Armenian groups.

So the question which needs to be considered is: what is the New Testament account of the church useful for, and in what ways is it misused?

One might argue that an overemphasis on “being like the first century church” – as some have put it, “following the pattern of the first believers” constitutes in some way a denial of a living, breathing body of Christ for all the centuries afterwards – as the believers of subsequent centuries have no voice to add to the conversation or incarnation of Christ in the Earth except for brief instances in which some small group of the body of Christ DID in fact look exactly like the first century. The problem with that however is that at no point in history did the body ever again look EXACTLY like the first century in form and practice and belief. For some, this is simply proof that the REAL body of Christ has ceased to exist ever since that time period, and that all that has existed since then has been a barren wasteland of false or tainted spirituality, with an occasional True Believer or two holding their own despite the flood of disappation. That though seems to me to be an extremely bleak view of God’s work in the Earth.

On the other hand, the testimony of the form and practice of the first century church in the Scriptures does seem to be a plumbline for something. The question is whether it is the form itself that is most to be emulated, or the dynamic of Christ within a group of people that resulted in the form. Even so, it is worth asking how much an organism which is constituted out of the same humanity with the same indwelling Christ could end up looking in any way substantially different in form if the DNA is the same. The analogy would be that aside from hybridization and cultivation, an apple tree from the first century would produce the same form, the same root system, the same fruit that an apple tree today would produce, not because the apple tree was trying specifically to mimic it’s 2000 year old ancestor, but because it has the same DNA. But then again, 2000 years of hybridization may also have yielded a somewhat different but useful result – and the same could be true of the forms that Christian practice has taken over the years.

So do we emphasize that the practices of the first century were due predominately to the rich dynamic of a people who had an extremely authentic seed of Christ in them and therefore their example from the first century is paramount (era-specific cultural interactions of course being accounted for), and this example in dire need of recapture above all else, OR, do we give equal weight to the findings and practices and teachings of subsequent generations, assuming that God was just as much at work in them as in the first century people?

My personal thoughts are that church history has much to teach us, so I can’t easily discount it – but neither can I quite trust it as much as I can trust those closest to the founding impetus and teaching of Christ. The first century believers had their human issues, but those human issues are only compounded by generation after generation of human issues. Still, I love the messiness of church history because God’s story of dealing with His people IS in fact still there – even if the first century is the best view, so I can’t utterly discard church history. Church history is also the best window on what happens to ideas and practices in the long term – and what happens when the faith is pressured by everything this world can throw at it over 1900 years of humans walking that out. And also, church history, as much as I entertain dreams of returning to century one, is where we are at and the only place we will ever be at – we can’t go back in time, so we need to accept that we’re part of the story of what happened afterwards, and how God interacted with Christ followers since century one. That’s my view…but what’s yours?

~Heather

July 23, 2015 at 5:10 am

Thanks for this article. Highlighting this issue is important because it is a juxtaposition. My own view is that when jesus said ‘this do….’ he meant ‘do what we are doing here when you meet to remember me. he never said it while preaching to the masses or even doing miracles. he said it while eating with disciples. To build upon this point the apostles went and replicated ‘this do…’ in homes. Paul corrects the Corinthians for not eating together 1 cor 11. I think we all need to get back to eating like a family and opening the scriptures in homes… simples!

LikeLike

July 23, 2015 at 9:08 am

“So do we emphasize that the practices of the first century were due predominately to the rich dynamic of a people who had an extremely authentic seed of Christ in them and therefore their example from the first century is paramount (era-specific cultural interactions of course being accounted for), and this example in dire need of recapture above all else, OR, do we give equal weight to the findings and practices and teachings of subsequent generations, assuming that God was just as much at work in them as in the first century people?” The presumption that those who came with Paul and there after got it right when they so skewed Jesus teaching that the Kingdom of God is within you precludes me from ordaining any of these options, but to choose the road into self. The real connection to Being

LikeLike

July 23, 2015 at 2:13 pm

Here is how I see the situation, I ask a different question. When did the church start misinterpreting Scripture? If you answer something like it never did, then you think the Roman church or Orthodox church is correct in its understanding; if you answer with some time period, then you are Protestant or Messianic. I think the church started to misunderstand SOME Scripture as early as the 2nd century and they were 180 degrees out of phase by the 4th century in SOME ways. My reasoning is that at first all the believers in Jesus were Jews who continued to practice Judaism, but by the 4th century such was prohibited. How does one get from 100% to a goal of 0% in a few hundred years? It was by misunderstanding the Scriptures they had.

LikeLike